I don’t remember what I had done to tick him off –maybe he had discovered I was stealing jars of syrup and selling them to buy cigarettes– but my oldest brother, John, told me to get out of the syrup factory he ran at the farm and stay out.

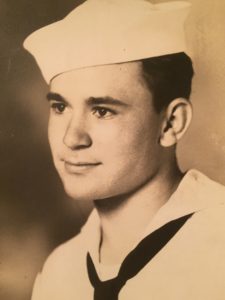

John, Dad called him “Mike,” was a grown man. He had been in the Navy during WWII and was 16 years older. I just a kid, eight or nine.

My first mother died when I was five and my second mother didn’t have much control over Brother Dave or me. I didn’t figure anybody could tell me what to do except Dad so I didn’t think John could make his order stick.

Dad had a strip mine near Altoona, AL, and he was there most days, digging coal, but not every day. So I waited. And when Dad stayed home one morning to take care of some business and he went out to the syrup factory, I followed him. He walked in and I walked in right behind him.

That was a mistake.

John grabbed me by the back of my belt and the collar of my shirt and threw me through an opening in the wall of the factory onto a coal pile outside.

NOTE: During World War II John gave up a deferment, joined the U.S. Navy, and then volunteered to serve on a submarine. He washed out of submarine school when one of his eardrum burst during a pressure test and ended up on USS Pocomoke (AV-9), a seaplane tender, in the Pacific.

Coming Monday: Making Boys Into Men