While cleaning up my tool room I found a small, empty container of Miracle Patching Cement and in that container were seven spoons and four forks, all in desperate need of polish.

Jack Hyland, my wife’s father, must have given them to me before he died 1986. I was going to take them to the cabin at Snowbird and put them to use but, somehow, that plastic container got shoved to the back of a shelf where it stayed for more than 30 years.

Yow!

* * *

Well, better late than never.

But before I took those spoons and forks to the mountain I needed to clean them up some and that’s when I noticed that all of them had writing on the back. One said “Victor S. Co.” Another said “Valencia Silver Plate.” And another, “1847 Rogers Bros. Adoration.”

One spoon was heavier than the others – silver, maybe? – and that got my full attention. On the back of that spoon these words had been stamped: “International Silver Co.” and a man’s name, “Fred Harvey.”

I began searching various Internet sites to try to find out if this was my lucky day. The answer was No. And Yes.

The International Silver Co. stamped its name on silver-plated, mostly worthless silverware. The company stamped its sterling silver, which was 92.5 percent pure silver, with the words “International Sterling.” So, no luck there.

Ah, but “Fred Harvey” was golden.

* * *

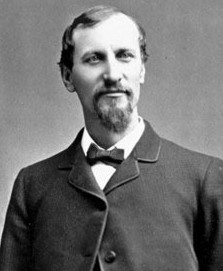

Frederick Henry Harvey was a rags-to-riches kind of guy, an immigrant who came to America in 1853 from Liverpool when he was 17 years old. According to Wikipedia, Harvey got a job as a pot scrubber and bus boy at a popular New York City restaurant and unwittingly began preparing for a career that would make him rich and famous, but not right away.

Harvey married, had six children, and, according to several web sites, worked at a number of jobs — on a river boat, in a jewelry store, a restaurant, and a railroad post office.

Harvey noticed that there were no good places for passengers to eat at the various stops along the rail line and he decided to fix that problem. In 1876, when he was 40 years old, Harvey got back in the restaurant business. Working with the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway he opened the first “Harvey House,” in Topeka, Kansas.

“Harvey’s meals were served in sumptuous portions that provided a good value for the traveling public; for instance, pies were cut into fourths, rather than sixths, which was the industry standard at the time,” according to Worthpoint.com.

Meals were served on fine China and Irish linens, the website said, and, I might add, with spoons so heavy you’d think they were made of silver.

The waitresses at his restaurants were called “Harvey Girls.”

“Placing ads in Midwestern and Eastern publications, he solicited women between the ages of 18 and 30 to travel west and work as waitresses in his restaurants,” according to Xanterra.com. “Other qualifications included being unmarried and ‘of good character.’ The ‘girls’ signed yearlong contracts and lived next to or in the Harvey Houses, under the close supervision of a Harvey Girl with the longest tenure. If they left before the year was up—the most common reason for doing so was marriage—they forfeited a portion of their base pay.”

Over the years thousands did get married. The humorist Will Rogers quipped that they “kept the West in food – and wives.”

The Harvey Girl idea was made into a movie. Old, old timers may remember a 1946 musical, “The Harvey Girls,” starring Judy Garland. A song from the musical, “On The Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe,” won an Academy Award for Best Original Song.

When Harvey died in 1901 there were 47 Harvey House restaurants, 15 hotels and 30 dining cars operating on the Santa Fe Railway — he is credited with creating the first “chain” restaurant in the United States.

And I own one of his spoons.

NOTE: The Fred Harvey Co. was sold in 1968, but some of its restaurants are still in operation.

Coming Friday: “This Is What Democracy Looks Like”