When my Dad went broke mining coal in the early 1950’s he moved his wife and two youngest sons from Gadsden, AL, to Charlotte where he had managed to hang on to his syrup plant.

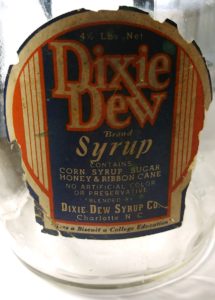

I worked there when I was a boy, starting when I was 13 or 14 years old, making Dixie Dew Syrup, an excellent honey flavored syrup.

And then, in the late 1950’s, Dad sold Dixie Dew, formed a new company called Hangwell Hanger, and began manufacturing clothes hangers. His clothes hanger plant was a sweat shop in every sense of the word — dirty, deafening, dangerous, and hot.

The plant where he manufactured syrup and, later, clothes hangers, was in the basement of a building on Graham Street in what is now part of the parking lot of the stadium where the Carolina Panthers football team plays its home games.

The clothes hanger plant was really hot. The only fresh air came through several barred half-windows on one side of the basement. We worked stripped to the waist.

It was smoky, too. The clothes hangers were dipped in black paint and then baked dry in an oven Dad designed and built. He didn’t vent the heat that boiled out of that oven, of course, or the smoke. By 10, 10:30 in the morning a blue haze permeated that basement.

Dad paid me 50 cents a hour. Adjusted for inflation that would be about $4.65 an hour now, well below today’s pitiful minimum wage of $7.25 an hour.

I ran two of the four clothes hanger machines, loading them with straight wire the machines bent and twisted into hangers, and taking off the finished hangers. Dad did not allow an operator to stop a machine to take off hangers, that had to be done of the fly, when the arm picking up the next hanger was descending and before it came back up. Your timing had to be perfect.

Why?

My father had put an electrical “stop” on each machine that would automatically shut it down when it malfunctioned and began ruining wire. Can’t have that, can we. But he did not insulate the “stops” so if the machine operator did not remove hangers smoothly, if the arm came back up and touch those hangers, the exposed electrical wires would shocked you into the middle of next week.

Some days the hangers would become tangled as they moved through the oven, which halted production. Dad would turn off the oven and wait impatiently as it began to cool. As soon as he thought it was cool enough, that is to say, as soon as he thought the heat wouldn’t kill me, he would sent me into the oven to untangle the hangers.

Why me?

I was the smallest one, an advantage inside the oven. And, to his credit, if someone was put at risk it had to be him or one of his boys.

Here’s the bottom line on my father as an employer: If OSHA inspectors had been around in those days they would have put him under the jail.

Oh, you want more proof?

OK.

One winter day in the early 1960’s, when I came home from college to see my finance, Donna Joy Hyland, I drove over to Davidson Street in North Charlotte to get a look at my Dad’s “new” plant. By that time he was out of the clothes hanger business.

I recognized some of the men working there and we said hello. One man was running a punch press, making pot holder looms. Another was running a machine Dad salvaged from his defunct clothes hanger business, straightening and cutting wire at an angle so it could be used to put up insulation. Dad called them Tiger Teeth and he made and sold a gazillion of them.

It was cold in the plant, in the 40’s. One of the men I knew asked me to ask Dad to let them have a kerosene heater. I said I would and when I went into his toasty warm office, I did.

But Dad said No.

You want to know why?

He said the men worked faster when they were cold.

*If you look closely at the ingredients on the label you’ll see that Dixie Dew also contained “ribbon cane.” But it didn’t when Dave and I were making it. That label must date back before our time, when ribbon cane was part of the formula.

Coming Monday: Get Dressed, Please