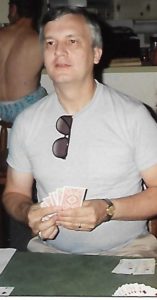

One of my brothers-in-law, Sherm Williams, liked to play Hearts and he loved to “run.” He was an excellent card player and he ran a lot. He made a lot of slams in Bridge, too.

But when we played Hearts I don’t think he played to win. He played to run, and “held” to run almost every hand, almost always passing hearts if he didn’t have more than three. That’s all the cards you’re allowed to pass, three, and he would void in hearts if he could.

I can’t teach the uninitiated how to play Hearts right now, but here’s a quick primer on running: To run –shoot the moon, it’s called — you have to capture all 13 hearts and the queen of spades. It may seem odd to people who don’t play Hearts but the best way to get all of them is to start with no hearts in your hand, or only the top hearts, the ace, king, or, if you’re real lucky, maybe even the ace, king, queen, jack.

Why?

Well, if you have a nine, or a ten, or even king of hearts in your hand, without the top cards, how are you going to win that trick? When you play the ten, or the king, someone is going to take it, or should, and your run –and the minus 26 points that goes with it– is gone. Instead of getting minus points, which is good, all the hearts you’ve taken that hand [and, maybe, the queen of spades, too, which counts 13 by itself] are going to count as plus points, which is bad. In Hearts, the player with the lowest score wins.

Anyway, I got a little tired of Sherm running, especially when he ran after one of my boys, Bo or Mark, had passed to him.

You can really hurt a “runner” by passing him or her a middling heart every time, and, if you have a stopper — a higher heart– keeping it. He’s not going anywhere if you pass him, say, the nine of hearts and you keep the jack and three little hearts. Even if he has the ace, king, queen, he can’t pull your jack, and when he plays the nine, you take it and stop his run.

[OK, OK, for those of you who are Hearts players, I know, it is still possible for a “runner” to get away under those circumstances if hearts are led through the player with the “stopper” and the runner has one or more of the top hearts. The “runner” takes the “stopper” card, say, the jack, with the ace and then he or she is off to the races.]

One night before we played I told my boys, listen up: If he runs tonight and you’ve passed to him, and you had a middling heart to give and you didn’t give it to him on the pass, I’m going to deal with you when we get home.

Would I really have really done that, give them licking for not passing a heart? Oh, surely not.

But I got my boys’ attention.

Sherm didn’t run that night.

Coming Monday: Was This God’s Hand At Work?