I thought for a while there I was going to be fired.

In August 1960, barely two months into my newspaper career, I wrote what newspaper people call a “color” story on a Southeastern Regional Babe Ruth tournament game – Ocala, Florida vs. Charlotte, North Carolina. The game had ended with a controversial strike three call against a Florida player and the home team won, 3-2.

The coach of the visiting team was pretty mad. He told me that the home plate umpire was a “blind man” who had committed “highway robbery.”

“You tell Charlotte,” the Florida coach said, “to keep that umpire and they’ll win the World Series.”

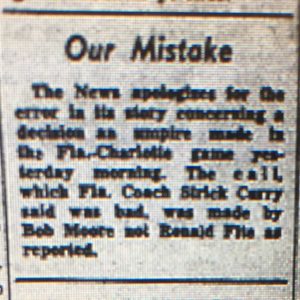

I wrote a story for The Charlotte News in which I quoted the Florida coach and identified the blind robber as Ronald Flie. But, it turned out, Mr. Flie wasn’t a blind robber. The umpire behind the plate that day was another man named Bob Moore.

Yow!

Umpires are called bad names all the time but not like that, not when they weren’t even in the game.

* * *

My boss, Sports Editor Bob Quincy, was out town so, next day, the other guys had to make the call. They decided to retract the story, which is not the same thing as a “correction.” I think a retraction was overboard but, whatever. Let’s just say they erred on the side of caution.

The day after that Quincy The Terrible came back and, after the first edition deadline, he called everyone over to his desk. He was steaming.

The error was mine and mine alone, but Quincy did not say one word to me. I guess I was just too far down on the totem pole for him to mess with. Instead, he went after Bob Myers, who had covered the game and who, Quincy said, should have kept me out of trouble.

How could Myers have done that? I have no idea.

Quincy didn’t like that retraction either. He said they should have corrected my error in the next day’s tournament story and moved on. That, in my opinion, would have been too little — we should have just run a correction.

That error turned out to be one of those blessings in disguise — I never forgot that sick feeling it gave me. Over time, especially when I began doing investigative work and dinging people on a regular basis, I became a fanatic about accuracy. I am not saying I never made another mistake. I did. But not often.

NOTE: I was so lucky to have started out on the sports desk of The Charlotte News. It was a small staff, only five guys, but they were all good ones. Three of them were later inducted into what is known now as the N.C. Media and Journalism Hall of Fame: Max Muhleman, Ronald Green Sr. and Quincy, posthumously in 2005. How I wish Bob had lived — he and I were inducted on the same night.

Coming Friday: Studying for the GED