Dixie Dew Syrup saved my family.

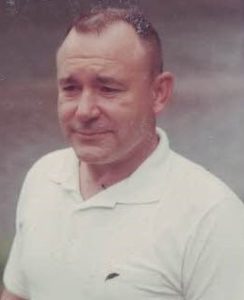

Dad got into the syrup business to persuade my mother to come back to him and he stayed in it because, for 30 years, it was his one, constant, money maker.

* * *

My family was destitute in the mid-1920’s forcing my mother to take the three children and go back to San Francisco, to her parents.

In 1926 Dad had moved the family to Coalburg, a coal mining town near Birmingham, and went into the house wrecking business.* According to Brother John, our father made “a lot of money” in the wrecking business but got bored and turned to poker for relaxation.

“He was good at many things, but he was not a good poker player,” John Franklin Stith Jr. said in a personal history he wrote in the 1980’s.

By the time the third child, Jane Cameron Stith, was born in August, 1927, John said, the family lived in a house with holes in the walls “big enough to throw a cat through,” my oldest sister, Marge, told me. Later that year, or early 1928, my mother left my father and took their children to San Francisco.

John said Dad wrote to Alice, our mother –he called her “Mickey” — telling her of his love and need for her and urging her to come back to Alabama.

“But Alice wanted more than talk; she wanted proof positive that the family would never again suffer the financial straits they had endured,” John wrote.

Two of the letters Dad wrote survived and one of them explained, in part, how he persuaded her to come back, and how our family survived numerous financial crises over the next 30 years.

He bought a honey-flavored syrup called “K-O,” formed the Pioneer Syrup Company Inc., and talked family members into investing in his business. In one of letters he wrote my mother he said that three of his five sisters and his mother had invested in his company: Nettie invested $1,500 [the equivalent of $22,707 in 2019 dollars; Ruth, $400 [$6,055 today; Bessie, $100 [$1,514]; and his mother, Annie Belle, $500 [$7,569] — a total of $2,500 cash — $37,845 in 2019 dollars.

Dad said he invested “$2,000 on credit with the privilege of buying an additional $500 making a total of $5,000.” He told mother that he had paid $500 in cash for the K-O formula but, apparently, he did not invest one dollar of his own money in Pioneer Syrup Co.

“The challenges and obstacles in starting a new business and marketing a food product were like gasoline on Jack’s fire,” John wrote. Dad’s name was John, but many people called him Jack.

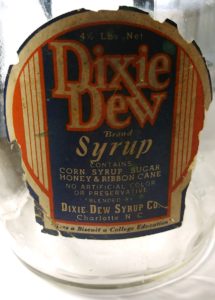

With capital provided by his mother and sisters, Dad bought property at 1023 Hoke Street, in Gadsden, AL, and built a syrup plant and a four-room house. He changed the “K-O” name to “Dixie Dew” and he gave his syrup a motto: “Gives A Biscuit A College Education.”

“He soon became known in every wholesale grocery house and hundreds of retail grocery stories within a 100-mile radius of Gadsden. He sent pictures and figures to Alice.”

She was impressed, John wrote, but not convinced until Pioneer Syrup Co. paid its first dividend.

“Alice felt this was a good an indicator of financial security as she would ever have, so it was time to go home,” John said.

In November, 1929 — a month after the stock market crashed and the Great Depression began — Alice arrive by train in Attalla, AL, bringing with her their three children: Marge, 6; John 3, and Jane, 2.

Dad and a partner he later acquired, Curt L. Rogers of Charlotte, sold Dixie Dew in the late 1950’s and Dad went into the clothes hanger business, which was sort of like swapping a silk purse for a sow’s ear.

NOTE: For a list of the 40-some jobs, or business, Dad was involved in see “My Father’s Advice: Don’t Do What I Did.”

John wrote this about Dad’s business acumen: “I have spent a great many hours trying to understand this complex man to whom everyone seemed drawn. He was a good money maker, but a very poor money manager. He spent his life trying to get ‘over the next hump’ that would lead to prosperity in some project or endeavor. Yet, when one of these efforts did begin to run smoothly and make money, he lost interest in it. He not only lost interest, he invariable drained the resources of the successful project to point that almost guaranteed it’s failure.”

*Dad told me the first time he got a contract to tear down a house he had no tools and no money to buy tools. He said he went to a hardware store and picked out a crowbar and a hammer. He said he told the clerk, I don’t have any money, but I’m going to earn some money with these tools and when I do I’ll come back and pay for them. If I have to fight way my way out, I will, but one way or another I’m going to leave here with these tools. He was immediately extended credit. And later, he said, he paid what he owed.

Coming Friday: Strange But True – Parts 3, 4 &5