It all began with Jayne Mansfield, an exceedingly well endowed actress popular in the 1950’s and early 1960’s, who claimed to have been lost at sea on Feb. 7, 1962. Whether she really was lost at sea I don’t know but I sort of doubt it.

Anyway, Journalist Third Class Gary D. Greve and I put out a daily paper when we were overseas so the crew of our ship, USS Los Angeles (CA-135), would have some idea of what was going on back home. Greve, who had also worked for a newspaper before he joined the Navy and was senior to me, was the editor, thank goodness.

There wasn’t much to our little newspaper. Stories were radioed to our ship. We typed them on mimeograph paper, the ship’s print shop ran off about 400 copies on 8 x 10 paper, stapled them together, and left stacks of them here and there in the passageways. Not much to it but since our paper was the only one around it was avidly read and passed around among the ship’s 1,000-man crew.

We ran a short item about Miss Mansfield’s boat capsizing but, as sometimes happened when we were overseas and radio traffic was interrupted for one reason or another, we didn’t learn for several days that she had been rescued.

When we found out that Miss Mansfield was safe our boss, who was a lieutenant junior grade, decided to have a little of what he called fun.

A friend of his had worked for the Associated Press and could write stories that read just like the real thing. Between them they cooked up an explanation for Miss Mansfield’s survival –the buoyancy of her bosoms.

He told Greve to put the phony Mansfield story in paper.

Greve did not like the lieutenant –hated him is more like it– and he certainly didn’t like the idea of putting a made up story in his newspaper, but for some reason he did it. And no one was the wiser.

The lieutenant loved it, and his private little joke emboldened him.

After the success of the made-up Mansfield story, the lieutenant and his friend, the former Associated Press reporter, decided to go big: they fabricated a story about an epidemic of rats in Long Beach, California, our ship’s home port.

Rats were everywhere, the story said.

When the mayor of Long Beach drove to Pier Echo to get a first-hand look, the rats attacked. The mayor barely escaped. Surrounded by rats, he was plucked from the roof of his car by a helicopter, the story said.

And there it was, a few graphs down, the local angle.

The story said the heavy cruiser Los Angeles, on its way home from the Western Pacific, was expected to tie up at Pier Echo within the week. That sentence, at least, was a fact. The LA had already left Hawaii, headed home.

The lieutenant told Greve to put the rat story in the paper, but Greve didn’t do it. The next day he told the officer there had been too much news, and not enough space left to run the rat story. Well, the officer said, get it in there tomorrow. But Greve held the story again.

That’s when the lieutenant told Greve, “I’m ordering you to put that story in paper.”

The trap was set.

I did mention it, didn’t I? Greve hated the lieutenant.

Continued tomorrow: Rat Remorse, Part 2 of 3

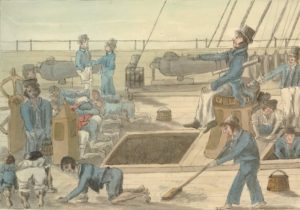

pump wet the deck with seawater, and men with buckets cast sand over the planks. The watch then scoured away the previous day’s dirt and grime with soft white stones and stiff brushes. Some believe “holystoning” got its name because scrubbing sailors looked as if they were kneeling in prayer. This was the “most disagreeable duty in the ship,” wrote Samuel Leech, a sailor aboard during the War of 1812, especially “on cold, frosty mornings.”

pump wet the deck with seawater, and men with buckets cast sand over the planks. The watch then scoured away the previous day’s dirt and grime with soft white stones and stiff brushes. Some believe “holystoning” got its name because scrubbing sailors looked as if they were kneeling in prayer. This was the “most disagreeable duty in the ship,” wrote Samuel Leech, a sailor aboard during the War of 1812, especially “on cold, frosty mornings.”