I was hitch hiking home, to Charlotte from Chapel Hill, and I was a little down.

It was Thanksgiving of my freshman year at the University of North Carolina and my grades were not as good as I had hope they would be: Two or three “A’s” and “B’s,” a “C” or two and a “D” in Spanish. School was harder than I had expected, especially Spanish.

When Charles Bernard, the man who gave me a ride, introduced himself, I knew who exactly who he was. He was UNC’s director of admissions. Earlier that year, when I applied for admission, I had written to him a couple of times.

When I told him my name he repeated it, “Stith. You just got out of the Navy, didn’t you?”

“Yes sir,” I said.

“Went to Charlotte Garinger.”

“Yes sir.”

“Didn’t study very hard in high school, did you.”

“No sir, I didn’t,” I said.

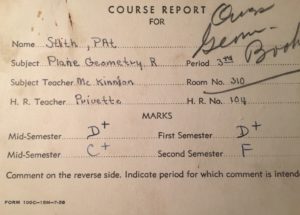

I had failed four subjects in high school: Latin, Biology, Plane Geometry and College Algebra. But, just before I got out of the Navy, I had tested OK on the SAT. And, in high school, I had been a National Merit Scholarship semi-finalist. I skipped the test to try to qualify as a finalist after my high school adviser told me that no college in America would give me a scholarship.

Mr. Bernard said his office had written my high school advisor asking whether she thought I ought to be admitted to UNC, and she said, “No.”

But because I had tested OK he figured I could do the work and because I had been in the service he figured that, maybe, I had grown up. So UNC decided to admit me anyway.

Mr. Bernard said that after his office notified my high school adviser that I had been admitted my advisor wrote back with a question of her own: “Why?”

If I had any doubts about getting my degree, and about graduating in four years, they disappeared right then.

Coming Friday: Black Belt