I had only been on the Appalachian Trail for 28 days, attempting to hike from Georgia to Maine, when I decided to go home and see a doctor.

I thought I had a hernia. Turns out, I was right.

Dr. Christopher Kenney, a surgeon, told me I had two choices: undergo an operation the following week and delay my hike a total of seven weeks or put on a girdle and go to Maine. I put on a girdle, a six-inch wide elastic band around my gut, and returned to the trail on March 21, 2015, seven days behind.

Friends I had been hiking with, including the Hiking Vikings, were long gone, more than 100 miles ahead of me. But Viking got shin splints and he and his hiking partner, Sharon McCray, had to slow down. From entries they made in trail journals at various shelters I could see that I was reeling them in — I gained four days in the first two weeks.

And then Nate got well and I was barely able to keep up. I was still two and a half days behind when I got a text from Sharon, on April 12, asking for a favor. Nate had left it hanging on a nail at Pickle Branch Shelter. She asked me to check when I passed by and get the ring if it was still there. I said I would and, much to my surprise, it was.

Meantime, Nate had asked Sharon to marry him, and she had said Yes! They sent me a video of that moment, made at McAfee Knob, the most iconic overlook on entire A.T.

I texted Sharon and asked if the ring I had found was “a ring” or “the ring.” She replied that it was “a ring” but, she said, it had a story.

I was still two days behind when the trail entered the Shenandoah National Park, in northern Virginia. The Shenandoah is easy trail compared to the rest of the A.T. so I laid my ears back and went all out to catch them. In four days I hiked 106 miles and, after dark on a cold, rainy, Saturday night, April 25, five weeks after I returned to the trail, I caught them at Tom Floyd Shelter.

I returned the ring, and Nate told me the story.

He said he believed in asking a woman’s father for his blessing before asking his daughter for her hand in marriage. But Sharon’s father was dead. So, Nate said, he talked to Sharon’s father in his thoughts, and asked for his blessing.

That’s when he found the ring, almost completely covered in dirt, barely visible. It was, to him, her father’s answer: “Yes.”

Postscript: Nate and Sharon completed their hike of the A.T. on July 12, 2015, and were married 10 days later. The Ring is Nate’s wedding band. They now have three boys.

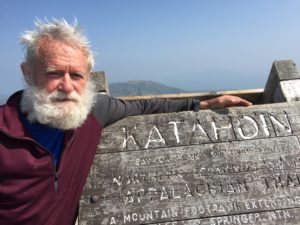

I completed my hike on July 14, 2015, and underwent surgery on Aug. 10.

Coming Monday: The Unlucky Forger