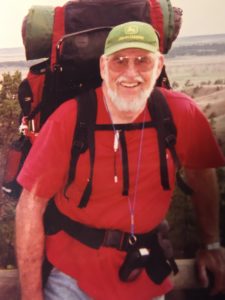

Mickelson Trail, South Dakota: My first hike.

Day One: Lynn Muchmore and I planned to start in Edgemont, S.D., and hike north through the Black Hills to Deadwood. The 109-mile Mickelson Trail, an old railroad bed, was wide and smooth, a walk in the park compared to the Appalachian Trail, and a lot more scenic.

I didn’t know it but I was carrying way too much weight –43 pounds –double the weight I usually carry now.

[Pack weight, pack weight and pack weight are the three most important things about back packing.]

That first afternoon we hiked out of town, into the hills, about six miles, and camped in a clump of trees beside the trail. My feet blistered a little but I ignored them. Gotta be tough, I thought.

[If and when your feet begin to heat up you have to do something about it immediately.]

Day Two — The scenery was stunning and Lynn said the northern end of the Mickelson Trail would be even better. It was hot, sunny, my ears and neck got a little red. We did 21 miles before I yelled “Uncle!” Lynn could have done 25 or 30 but I was having a hard time. My left heel was a bloody mess with a patch of missing skin the size of a silver dollar; the blister hadn’t broken yet on the other heel.

Late that day, to lighten my load by two pounds, I poured out a liter of water. What was I thinking?! I was thinking I could get more water when we camped. I was wrong.

[Food you can do without. Water is everything, especially when you don’t have it.]

I skipped supper –I had no water to rehydrate my food– pitched my tent near a highway bridge and crawled into my sleeping bag, hurting and so thirsty.

Day three — It was 17 miles to Custer, S.D., which was looking like the end of the trail for me. My feet were ruined but all I could think about was water. We hiked six more miles that morning before we came to a tiny town with a restaurant that served the best water I ever tasted. Breakfast was good, too.

Eleven miles to go.

Lucky for me, I guess, the weather had turned real bad north of Custer. Lynn didn’t want to hike in crappy weather and I couldn’t. All I had to do was make it to Custer.

With six miles to go the bad weather reached us and it began to snow. What a state, a blistering hot sun one day and snow the next. Lynn offered to walk to Custer alone and come back for me in a cab. It was good of him, really. But I would rather have rubbed my heels with salt and crawled to Custer than ride there in a cab.

Postscript: I made it.

For the next few days I wore socks but no shoes and Lynn and I went sight seeing. There’s lots to see in that part of the country, including Devil’s Tower and the Badlands. One day we went underground, down into a decommissioned U.S. Air Force silo that had once held a nuclear-tipped Minuteman intercontinental ballistic missile. On the steel door leading to the missile silo someone had drawn a pizza box lid and written these words: “Delivered hot anywhere in the world in 15 minutes.”

Why is that?

Lynn and I went to several museums in South Dakota I saw exhibits on Wounded Knee and Little Big Horn where the solders of the U.S. 7th Cavalry and Indians fought, and it got me to wondering.

Wounded Knee, where, according to the National Park Service, 153 Indians [including women and children] and 25 soldiers of the U.S 7th Cavalry were killed, and prisoners were taken, is called a “massacre.”

Little Big Horn, where all 210 soldiers under Col. George Armstrong Custer’s immediate command were killed [Indian casualties are unknown], and no prisoners were taken, is called a “battle.”

Why is that?

Coming Monday: Blame It On Youth