It was after 10 on a Saturday night when my home phone rang. I answered. The caller identified himself as an IRS special agent from Atlanta; he wanted to meet with me and talk.

He didn’t say what he wanted to talk about and I didn’t ask. I knew. He was in Raleigh to plug a leak. He said he was staying at the Holiday Inn on Hillsborough Street in downtown Raleigh and I agreed to meet him there the following day, on Sunday morning at 10.

He wanted to know the name of the anonymous source of a story I had written saying the IRS had recommended prosecution of 13 men associated with North Carolina Gov. Bob Scott’s election campaign. No way would I ever tell him, but I agreed to meet because he might give me some information, inadvertently, of course. He couldn’t ask questions without giving away information. I knew that, because I was in the question asking business myself. I was an investigative reporter for The News & Observer.

After I hung up I got to thinking, did this guy really work for the IRS? How did he get my home number? It wasn’t unlisted, but it wasn’t listed under “Pat,” the name I’ve always gone by, either. Oh, I know, I know, he said he worked for the IRS and if he did, getting my phone number would have been child’s play, it’s right there on my tax return.

But I called The N&O anyway and asked the city editor, Gene Cherry, if anyone had called that evening looking for me, if he had given anyone my home telephone number.

“No, what’s up?” Gene asked.

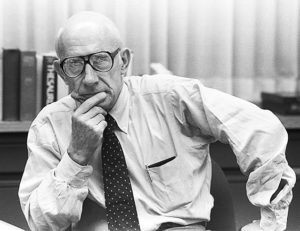

I told him and he told me to sit tight while he called called Claude Sitton, The N&O’s executive editor. A few minutes later Gene called back, gave me Claude’s number, and told me to call him.

I called Claude, told him what happened and he told me to forget about it — don’t meet with the IRS guy. And then he said, “Be in my office at 9 o’clock Monday.”

I followed Claude’s instruction, I stood the guy up.

A few minutes before 9 on Monday, I walked by Claude’s third floor office on the way to my desk in the newsroom. His door was open and I could see he had company: Bill Lassiter, an N&O attorney who worked on newsroom issues, and Frank Daniels Jr., the publisher. Nine o’clock came and went; I was not asked to join them.

Later I learned what happened.

Sitton, who had covered the civil rights movement in the South for The New York Times and, after he became executive editor The N&O, had won a Pulitzer Prize for Commentary, had a fierce temper. He was also protective of his reporters and this was just the sort thing that would set him off.

Claude had already gone to bed when the city editor called. After Claude and I talked he got dressed, called the paper and told them he was coming in, told them to have a reporter and a photographer waiting when he got there. And when he arrived, around 11 p.m. or little later, the three of them went to the Holiday Inn.

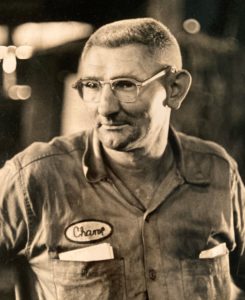

I don’t know how Claude got the guy’s room number, maybe he had given it to me and I gave it to Claude. Anyway, Claude knocked on his door and when the agent opened the door Sitton stepped back out of the way and the photographer took the agent’s picture, standing in the doorway, wearing pajamas.

That’s when the shouting started, I was told. Maybe that agent also had a temper. Anyway, Claude told him that if he wanted to talk to one of his reporters, he had to come in the front door of The N&O and get permission.

I guess you know the rest. He came to the paper that Monday morning but he was never going to get Sitton’s permission to question me about my source. And that was that.

Coming Friday: My Face Is Still Red