A cab picked me up in front of my hotel in Moscow at 8 a.m. sharp, just as my host said it would. Everything was going as planned.

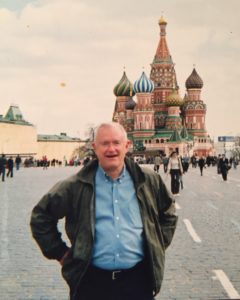

I had arrived the previous afternoon from New York, walked around Red Square, took photos of St. Basil’s Cathedral, and now I was ready to go to work. I was in Moscow to talk to Russian journalists about how investigative reporting is done in the United States or, at least, how I did it.

I didn’t know where my taxi was going — I didn’t have the address, the driver was just supposed to deliver me. I had been told it wasn’t far but the driver kept on driving, on and on. I couldn’t asked for an explanation, he didn’t speak English and I didn’t speak Russian.

Finally he stopped, reached over the seat, opened the back door nearest the curb, and motioned for me to get out. And then he drove away leaving me standing in front a tan colored, six or eight-story building that was, like most buildings I saw in Moscow, on the ugly side.

I soon discovered that he had not taken me to the place where I supposed to give a talk; he had taken me to the U.S. Embassy. This was a huge problem, maybe a fatal problem — my host didn’t know where I was and I didn’t know where I was supposed to be.

There were two guards in front of embassy. One appears to be an American and one a Russian. I spoke with the American and then, at his direction, went inside. Our embassy helps Americans in trouble, doesn’t it? And I sure was in trouble.

I had flown a total of more than 5,000 miles to make the opening speech at a meeting of Russian journalists and now, because of this SNAFU, it was starting to look like that might not happen.

The embassy fellow did help me.

He found the address of the outfit that had invited me — that’s not where I was speaking, but it was a start — and he wrote the address in Russian on a piece of piece of paper. I asked if he would call a cab for me. He said he could do that but it might be several hours before it arrived. There just weren’t enough cabs in Moscow, he said. And they weren’t reliable.

That part, the unreliable part, I already knew.

What I had to do, he said, was catch a car. Go back outside, he said, give this address to the guard, and asked him to catch a car for you.

Because taxi service is so poor catching cars is an everyday thing in Moscow. You hold up an arm, a car stops, and you tell them where you want to go. If it’s on the way to where they’re going anyway, you agree on a price, and get in. If it’s too far out of the way, or you’re not willing to pay what they’re asking, they drive away and you catch another car.

The American guard flagged down a ride, negotiated the price, I got in, and off we went, to where I had no idea. It wasn’t long before two things were obvious:

One, this guy didn’t know where he was going — twice he stopped to consult a map.

Two, he didn’t want any help from me, didn’t want to look at a map I had in my pocket.

He never smiled, never gestured to me. He gave every indication that I was a sack of potatoes to be delivered, nothing more. He drove on and on, turning this way and that, and, meanwhile — tick tock, tick tock — time was slipping away.

At last he stopped, got out, and motioned for me to get out. I followed him across the street to an alley between two buildings. On one side of the alley there were two armed men wearing camouflage uniforms, solders I assumed.

[I saw a lot of security men in Moscow: soldiers carrying automatic weapons posted at public buildings; plainclothesmen in the lobby of my hotel; and a guard at the door of a deli/liquor store I visited.]

We went down the alley, to the rear of a building and then inside where there was another guard lounging at the bottom of a stairwell. None of this, the alley, the back door entrance, the security, made a lick of sense to me. Was I in danger?

We went up three flights of stairs, to a door at the top of the landing. He knocked, and someone who worked for my host opened the door. This ill-tempered Russian had taken me right to the door of the place I needed to be.

Oh, yes, I tipped him. Generously.

Postscript: My host flagged down another car, and sent me on my way to the conference. I was a few minutes late, but not too late.

I think almost everything I told them was interesting but almost nothing I told them was relevant. Russian journalists don’t have the access to public records or to public officials that reporters here have. And working there can be dangerous. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, 38 journalists were murdered in Russia from 1993-2018. During that same period seven were murdered in the United States, including four at the Capital Gazette in Annapolis, MD, this past summer.

One of the Russian journalists I met in Moscow told me that when she goes to a press conference called by the mayor of the city she covers she is given a list of questions to ask. And what happens if she doesn’t stick to the script? She said she was not allowed to attend the next press conference.

I fear that some Americans, those who consider the press “the enemy of the American people,” would like to stop reporters here from asking questions not approved in advance by the mayor, or the governor. Or the president.

Coming Monday: The Peacenik Band