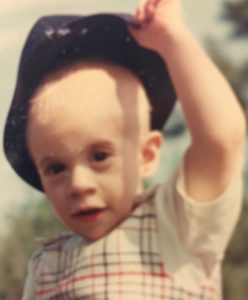

Long before we were given the official verdict, before we took our 18-month old son to North Carolina Memorial Hospital in Chapel Hill for a battery of tests, we knew.

The thoracic surgeon who had operated on Jack’s sunken chest [pectus excavatum] told my wife, Donna, and me that that was the reason Jack was so far behind. After the operation, he said, Jack would catch up with his twin brother, Mark.

But in our hearts we knew better.

I hated to give Dad the official verdict from the doctors in Chapel Hill. Not because he would take it hard. I hated to tell him because he wouldn’t take it all. He would scoff at the diagnosis. I didn’t want hear that. It was time to play the cards we had been dealt.

I had often heard Dad brag — or maybe he was just giving thanks — that all of his grandchildren were perfect. No birth defects. But that won’t true now. His 13th grandchild had been hit by the bullet.

He and I were alone at the box shop, at Queen City Container in Charlotte, on a Saturday morning, when I told him, short and to the point: “The doctors in Chapel Hill say Jack is profoundly retarded.”

For a second or two he didn’t say anything. And then he said to me, “Everybody has a cross to bear and this is yours.”

That was it. He didn’t say another word, then or ever.

Coming Monday: The Quick Fix