Big Mouth started touting the Toe River while we were on another white water trip, on the Chattooga down in South Carolina. When we were done with Chattooga, he said, he’d take us on a real white water river.

I had never been on the Toe, which, like Chattooga, starts in the mountains of North Carolina, didn’t know anything about it. But I doubted it had better rapids than the Chattooga –“the ultimate and ideal for the undecked canoe” — and, even if it did, he ought not be talking about the Toe, not with a bunch of guys getting ready to go down the Chattooga. That’s bad form.

When we got back to Charlotte a buddy and I decided we’d make him put up or shut up — we’d run the Toe with him. Wouldn’t be same as Chattooga, of course, where we were in canoes. On the Toe the three of us would be riding single in two-man rafts, which are a lot more stable, a lot harder to turn over.

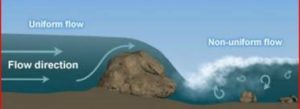

On the way to the mountains Big Mouth kept talking about the Toe, and how we better be careful. He said some rapids had what they call hydraulics,* an area below the rapid where the flow of the water reverses. He said a hydraulic could grab your raft and pull it — and you — backwards, under the falls.

Finally we were in the water, and I was alone in my raft. The Toe, in a raft, wasn’t as challenging as Chattooga, but it was fun. Beautiful, too.

Then I went over a three or four-foot fall and my raft stopped. Water rushed by, but my raft didn’t move. Something had me. In a one second I went from having fun to fighting for my life. Everything Big Mouth had said about hydraulics that morning came rushing back and I paddled as if my life depended on it.

My friends could see what was happening, could see I was caught, but they couldn’t help me. In fast water you can’t paddle a raft upriver, or straight across a river — the current won’t allow it.

There’s only so long you can paddle with all your might but, as I slowed down, I could see my raft wasn’t going backwards, wasn’t getting closer to the falls.

Finally I quit padding altogether. Nothing happened. My raft just sat here, a few feet below the falls. Had my lead line, a rope attached to my raft, snagged on a rock or something? I checked. No, that wasn’t problem: I was caught in a hydraulic.

I sat there a few more seconds trying to figure out what to do. But you can’t just sit there all day. I decided to grab the lead line and roll out the front of the raft. When I hit the water the current carried me away; my raft stayed put. When the rope went taunt I yanked and and my raft came to me.

Then I went back and ran the thing again. My friends did too. Fun ride.

- Wikipedia says a hydraulic is formed when water pours over the top of a submerged object, or underwater ledges, causing the surface water to flow back upstream toward the object.

Coming Friday: Don’t You Just Hate Being Right Sometimes