Dean Smith coached the University of North Carolina basketball team for ten years, took his team to three Final Fours, and won the National Invitational Tournament before UNC began paying him as much as it paid its football coach.

UNC, whose basketball teams have been to the Final Four 20 times, more than any other team in the country, used to be a football school — and not all that long ago, either. Not a good football school, mind you, but a school where football was more important that basketball.

First, the obvious, and then I’ll tell you about the salary figures I stumbled across last month while looking up something else at UNC’s Wilson Library.

The Obvious: Facilities

The Tar Heels have played football in Kenan Stadium since 1927, a stadium that originally seated 24,000. Over the years UNC more than doubled the size of the stadium and upgraded it in every respect. It doesn’t seat anywhere near as many as the stadiums where today’s football factories play ball, but it’s in the middle of the campus, almost surrounded by trees, and way more beautiful than most stadiums.

Meanwhile, from the early 1920’s to the late ’30s, Tar Heel basketball teams played at Indoor Athletic Center, better known as the “Tin Can.” It looked like a great big tin shed, the kind you might find on a farm, where they stored the tractor and plows.

George Shepard, who won 81.2 percent of the UNC basketball games he coached during his four year tenure [1931-35], had this to say about that old venue, according to Wikipedia:

“The Tin Can was always freezing […] they had icicles in the corners. To stay warm the electricians put those big-wattage bulbs under the benches, and we had blankets and wore heavy sweat clothes.”

The basketball team moved to Woolen Gymnasium in 1938, where it was still playing ball when I enrolled at UNC in the fall of 1962. Woolen was just a big high school gym, with pull out bleachers and a capacity of about 5,000. That’s where they were playing when Coach Smith was hired in 1961, an overgrown high school gym.

In 1965 the team moved into the shiny new but only slightly larger Carmichael Auditorium, where most fans could sit in chairs instead of on bleachers.

The UNC basketball team did not get an arena equal to –or better than– Kenan Stadium until it moved to the Dean E. Smith Center, better known as the Dean Dome, current capacity, 21,750, in January 1986, after Smith had coached the team for 25 years.

The Money

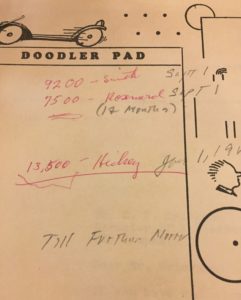

Hand written notes on a scratch pad in a file that had belong to Vernon Crook, UNC’s assistant athletic director for business, say that in 1961, when Dean Smith was hired to coach the university’s basketball team, UNC paid him an annual salary of $9,200 [$77,551 in 2018 dollars].

Hand written notes on a scratch pad in a file that had belong to Vernon Crook, UNC’s assistant athletic director for business, say that in 1961, when Dean Smith was hired to coach the university’s basketball team, UNC paid him an annual salary of $9,200 [$77,551 in 2018 dollars].

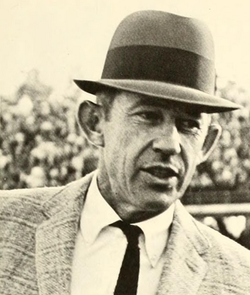

UNC’s head football coach, Jim Hickey, was paid $13,500 [$113,417 in 2018 dollars] effective Jan. 1, 1962 – 46 percent more than Smith.

Was Hickey a big winner?

No. He was the football coach. In the 1959, ’60 and ’61 seasons Hickey’s teams lost more games than they won. And, except for one terrific year, his teams continued to lose. Hickey coached a total of eight years at UNC, 1959-1966, winning 36 and losing 45.

UNC paid Hickey $17,500 in 1966, [$135,712 in 2018 dollars] his last season. He won 2, lost 8 that year. Smith was paid $12,600 in 1966-67 [$97,713 in 2018 dollars]. His team won the ACC regular season and tournament championships and advanced to the NCAA’s Final Four.

Smith did not achieve pay parity with UNC’s football coach until 1971-72, when he and Bill Dooley, who replaced Hickey, were both paid $25,000 [$154,814 in 2018 dollars]. At that point Smith had taken his team to three Final Fours and won the NIT; Dooley had won 18 and lost 24.

NOTE: Dooley coached Carolina’s football team for 11 seasons and left with a record of 69-53-2, at that time a school record for wins by a football coach. Smith retired after the 1996-97 season with a record of 879-254, at that time a national record for wins by a basketball coach. His teams won two national championships.

Coming Friday: Looking In The Wrong Place

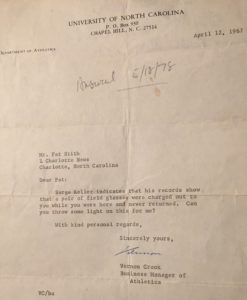

But somewhere along the way one pair of field glasses went missing. I turned in the other one and told my boss, Bob Quincy, the sports information director, what had happened — someone took the other pair.

But somewhere along the way one pair of field glasses went missing. I turned in the other one and told my boss, Bob Quincy, the sports information director, what had happened — someone took the other pair.