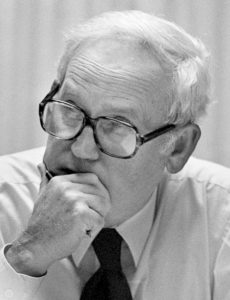

Bob Brooks, the managing editor of The News & Observer for most of my time there, sent the staff the most puzzling memo I had ever seen. The memo said reporters could not promise to protect the identity of a source without his permission.

I can’t begin to tell you how nutty that edict was. I talked to people off the record practically every day. Other reporters did, too. Any reporter who says he or she never goes off the record must be covering, I don’t know, the school lunch menu?

Bob was a good newspaperman. I respected him, I liked him, too. He couldn’t possibly be serious, could he?

So I went to his office, memo in hand, and asked him what it meant. He said he meant what it said — end of discussion. Bob had zero tolerance for anyone who challenged his authority.

I went back to my desk, sat down, and thought about it. Until recently judges had been citing reporters for contempt and putting them in jail when they refused to reveal the identity of a confidential source. But judges had finally wised up and realized that some reporters wanted to go to jail to protect a source.

So they quit jailing reporters and started fining their newspapers instead, up to $5,000 a day, a lot more in today’s money. I figured that must have been the reason for crazy memo: If one of our reporters refused to reveal a confidential source, and they hadn’t gotten permission from Brooks, The N&O would claim that the reporter had acted outside the scope of his or her employment. That’s the only explanation that made sense to me.

After that I didn’t worry about the crazy memo. I ignored it. I kept doing my job the way I had always done it. And, as far as I know, so did everybody else.

NOTE: By the way, “Off the record” and “Not for attribution” are not the same thing. Not for attribution meant I could use the information but I could never identify the source. Off the record meant I couldn’t do anything with the information without further negotiation. Most often the source would say I could use the information if I could find it somewhere else and he or she might tell me where I could find it. Or I could use it, not for attribution, after a certain date. The N&O stopped using anonymous sources in investigative stories in the late 1970’s.

Coming Friday: Nuts!