When I enrolled at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, in the fall of 1963, there were only 18 black freshman and no black faculty members. White women, in relatively small numbers, had attended the university for decades but 1963 was the first year women were admitted as freshmen in it’s fine arts program. So when I started school there almost every class was mostly white and mostly male.

I may have taken this particular class when I was a sophomore, I don’t remember, but I do remember exactly what happened.

The instructor asked for volunteers, got half a dozen, and sent them out of the room. He told the rest of the class that he was going to call those students back into class one at a time.

He said he would tell the first student he called back into the room this story:

A well dressed white man got on a bus, sat down in the front next to a white woman, and began to bother her. When other passengers tried to get him to move, he pulled a knife. At that point the bus driver stopped and made the man get off the bus. The story had a lot of detail I’ve left out, but those were the main points.

The instructor said that after telling the story to the first volunteer he would ask another volunteer to come back into the room. The first volunteer would then be asked to stand in front of the class and repeat the story to the second volunteer. Then the third volunteer would be asked to come back and the second volunteer would tell him the story. And so on and so forth until the story had been repeated by all the volunteers, including the last one who would repeat the story one last time to the class.

If one of those student left out some detail when he retold the story, that detail was gone forever, of course. And if he changed something, that change was repeated.

I sat there listening in amazement as the story was told and retold.

Before they’re finished, the instructor predicted, the white man would become a black man, the good clothes would turn into shabby clothes, and the knife would become a razor.

And that’s exactly what happened.

BACKGROUND: “In the spring of 1963, members of the Student Peace Union and town residents in the Committee for Open Business began demanding the integration of all public facilities. Pickets appeared during April in front of the privately owned College Cafe. Protesters launched street marches in May. In July, they increased pressure on the town council by mounting their first sit-in inside a business.” Source: The Carolina Story: A Virtual Museum of University History

Coming Friday: My One Star Hotel

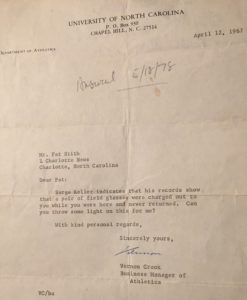

But somewhere along the way one pair of field glasses went missing. I turned in the other one and told my boss, Bob Quincy, the sports information director, what had happened — someone took the other pair.

But somewhere along the way one pair of field glasses went missing. I turned in the other one and told my boss, Bob Quincy, the sports information director, what had happened — someone took the other pair.