No. 1

My Dad gave me this tip in June 1966, a few days after I graduated from UNC and went to work fulltime at The Charlotte News, about a man who could stir molten aluminum with his finger. It was the only tip he ever gave me, but it was a good one.

In case you’re wondering, the melting point of aluminum is 1,221 degrees Fahrenheit.

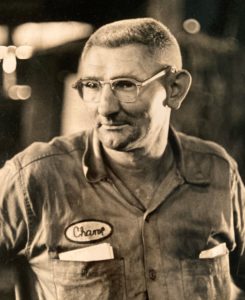

J.C. Champion was grey-headed at 49 with the calloused hands of a man who had worked in a foundry all of his life. He told me that his Dad, who had also been an foundry worker, taught him how to play with liquid fire when he was 16.

“There really ain’t nothing to it,” Champion said. “All it takes is nerve. It don’t burn any. Only about as much as running your finger through a pot of boiling water.”

While I watched, and a News photographer took pictures, Champion stuck his finger in a pot of molten aluminum and pulled it a half a turn, several times, until a little whirlpool of liquid aluminum appeared in the middle.

“If you was to do it just one time,” he said, “you wouldn’t even notice it. Now, a course, you do it over and over — it’ll give you a mild sunburn.”

Afterward, was his finger OK, in other words, did he still have it?

It was; he did.

I examined his right forefinger, the one he had used to stir the aluminum. It was slick and shiny and warm and a little browner than the others, but none the worse for wear.

NOTE: After I examined his finger Champion decided to show off a little. He walked over to where iron was being poured into a mold, studied it to see if if was hot enough, and then began knocking that stream of molten iron all over the floor with his finger.

“You got to be careful it’s hot enough,” he said. “You have to be sure it won’t stop moving and set up on you.”

Iron, by the way, melts at 2,750 degrees Fahrenheit.

* * *

No. 2

Raleigh’s police chief occasionally flew a psychic into town, at public expense, to consult on major unsolved murder and missing-person cases.

I kid you not.

A psychic, just to refresh your memory, is someone who is “sensitive to nonphysical or supernatural forces and influences; marked by extraordinary or mysterious sensitivity, perception, or understanding,” according to the Merriam-Webster dictionary,

The chief was also experimenting with birthday-based biorhythms, which he said sometimes predetermine a person’s good and bad days in cycles counted from the day of birth. The idea, he said, was to bring suspects in for questioning when they were at the “low point” of their cycle and have them interrogated by a detective who was at the “high point ” of his or her cycle.

I know. It sounds wacky because it is wacky.

Coming Friday: The Bachelor