I came within a nickel of drowning in the Chattooga River. Maybe I would have if it hadn’t been for my boys.

The Chattooga, which begins in Western North Carolina, near Cashiers, and runs southwest, between South Carolina and Georgia, is a National Wild and Scenic River. Some say that when the river is up Section Three is the ultimate and ideal challenge for a boater in an undecked canoe.

Back before the book and a movie of the same name, Deliverance, made the Chattooga famous, a bunch of us would to go down there on a Friday evening and camp by the river, at Earl’s Ford. Next morning we’d put our canoes in the water and paddle Section Three.

This trip was in December. The river was high, it had been raining a lot, but I had never overturned on previous trips and I had no intention of going down that day either. Way too cold for that.

But I did go down, in a place called The Narrows. The river, squeezed together, speeded up there. And the haystacks –standing waves — got bigger.

Brownsguides.com describes The Narrows this way: “Canyon walls pinch the water forcing currents to the bottom of the river to reemerge as ‘wave trains’ or a series of fairly uniform standing waves coming one right after another. The deeper the river the higher the wave trains.”

I don’t know how big they were that day, big enough to pour over the sides of my canoe and drive it under.

I was in trouble the moment I hit the water. It was so cold. And I hadn’t put my life jacket on properly, hadn’t tightened it around my waist. My life jacket flared out over my head and I went under.

There was no possibility of swimming to the bank — there was no bank — just rock walls on either side. The only way out was down river, through The Narrows.

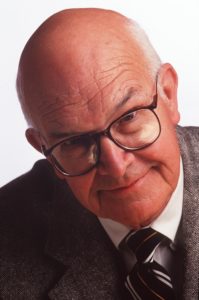

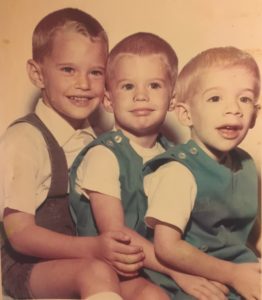

I was not afraid, that surprised me the most. Not afraid of dying, not afraid of drowning. And I was drowning, all I had to do was relax. And then I had a vision of my three boys.

I grabbed my life jacket, pulled it down between my legs and got my head out of the water. Between haystacks I could breath.

I had to get out of the river while I could still move. It was so, so cold. When the current ran me into a boulder near the end of The Narrows I grabbed my chance. I hauled myself out of the river and crouched there, shivering, waiting for my friends to come for me.

I was saved by a vision of the future I did not want: I did not want another man raising my sons.

Postscript: I stripped off my clothes, trying to get warmer, trying to stop shaking, and paddled the last few miles, to the take out at Highway 76, in my skivvies.

Coming Friday: SOB